Topic 2 → Subtopic 2.7

What is a Price Ceiling?

Imagine finding yourself in a bustling city where rents are sky-high, making it nearly impossible for the average person to afford decent housing. Or picture a scenario during a fuel crisis, where rising gasoline prices make it difficult for families to fill their tanks. These situations often prompt governments to step in and impose price ceilings, limiting how much can be charged for essential goods and services.

Price ceilings are widely used to make critical items like housing, energy, and healthcare more affordable, but they come with their own set of challenges. While the intention is to protect consumers, the effects often ripple through the economy, creating unintended consequences. To fully understand how price ceilings work, it is essential to explore their mechanics, their impact on surplus, and the broader implications they have for markets and society.

How Price Ceilings Work

A price ceiling sets a legal maximum price for a good or service. For it to have an impact, it must be set below the market equilibrium price—the point where supply and demand naturally balance. At this lower price, consumers want to buy more of the good, but producers are less willing to supply it, creating a shortage.

Take rent control as an example. Governments often cap rental prices to make housing more affordable, especially in expensive cities. While some tenants benefit from paying lower rents, landlords may reduce the number of properties they rent out or cut back on maintenance to manage costs. Over time, the quality and availability of rental housing decline, leaving many potential renters without accommodation.

Another example is price caps on essential goods like fuel during emergencies. When gasoline prices are capped, demand surges as consumers rush to fill their tanks, while suppliers struggle to meet the increased demand due to the artificially low price. This mismatch results in long lines at gas stations, empty pumps, and a growing sense of frustration among consumers.

Effects of Price Ceilings on Surplus

The introduction of a price ceiling reshapes the distribution of economic benefits in the market, affecting both consumers and producers. Consumers who manage to purchase the good at the capped price gain surplus, as they pay less than they were willing to. However, this benefit is not universal, as many consumers face shortages and are unable to access the good at all, resulting in lost welfare.

Producers, on the other hand, face reduced revenue because they cannot charge the equilibrium price. This decreases their surplus and may force some producers to exit the market altogether. The mismatch between demand and supply creates inefficiencies, including a deadweight loss, which represents the loss of total surplus due to transactions that no longer occur.

Long-Term Consequences of Price Ceilings

The effects of price ceilings extend far beyond immediate shortages. Over time, producers may leave the market or shift their focus to other, more profitable goods or services, exacerbating supply issues. For example, persistent rent control policies often discourage developers from building new housing, leading to chronic shortages in the long term.

Additionally, price ceilings can distort market signals, making it difficult for producers to allocate resources effectively. When prices are artificially low, there is no incentive to innovate or improve efficiency, which can stagnate industries and reduce the overall quality of goods and services.

Non-price mechanisms often emerge to allocate the limited supply, such as long waiting lines, favoritism, or black markets. These practices undermine the fairness and transparency of the market, leading to frustration and inefficiencies.

Broader Implications of Price Ceilings

Price ceilings are often implemented with the best intentions, aiming to address affordability and equity concerns. However, their unintended consequences frequently undermine these goals. Shortages, inefficiencies, and reduced quality can outweigh the initial benefits, particularly when ceilings are applied over the long term.

To mitigate these issues, policymakers may consider complementary measures, such as subsidies for producers or targeted assistance for consumers. These approaches can achieve similar objectives without the market distortions caused by direct price caps.

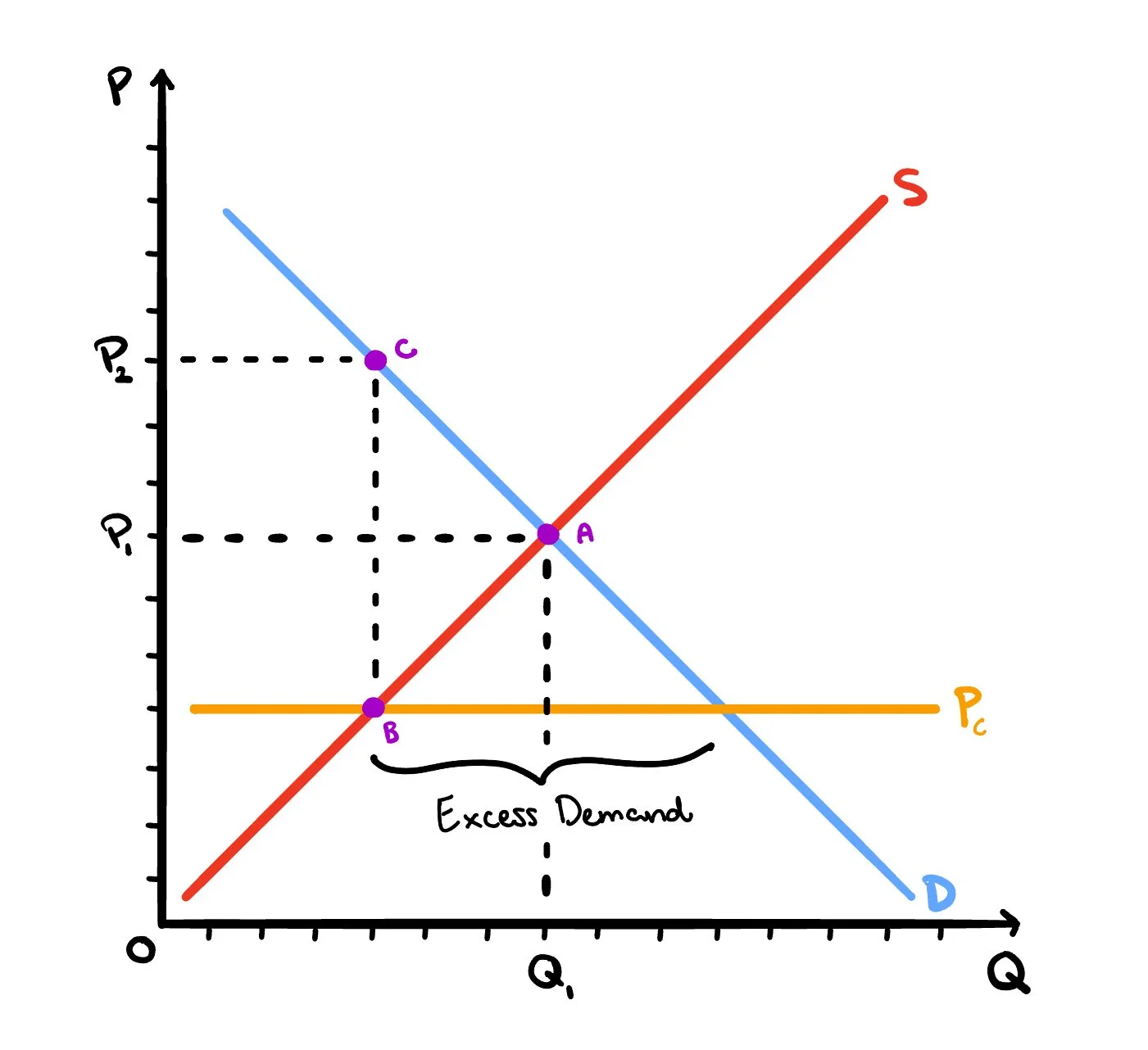

Key Graph to Remember:

Figure 1. Price Floors being set in a market, causing there to be excess demand

-

Description text goes here

Example:

During a fuel shortage, a government caps gasoline prices at $3 per gallon, below the equilibrium price of $4. Consumers flood gas stations, leading to increased demand for fuel, but suppliers, unable to profit at the lower price, reduce the amount of gasoline they supply. This creates a shortage, leaving many drivers unable to fill their tanks.

In Summary:

Price ceilings are a policy tool aimed at improving affordability for essential goods and services. While they can provide short-term relief for consumers, their long-term effects often include shortages, inefficiencies, and reduced quality. Policymakers must carefully evaluate these trade-offs and consider alternative strategies, such as subsidies or targeted assistance, to achieve their objectives without disrupting market dynamics.

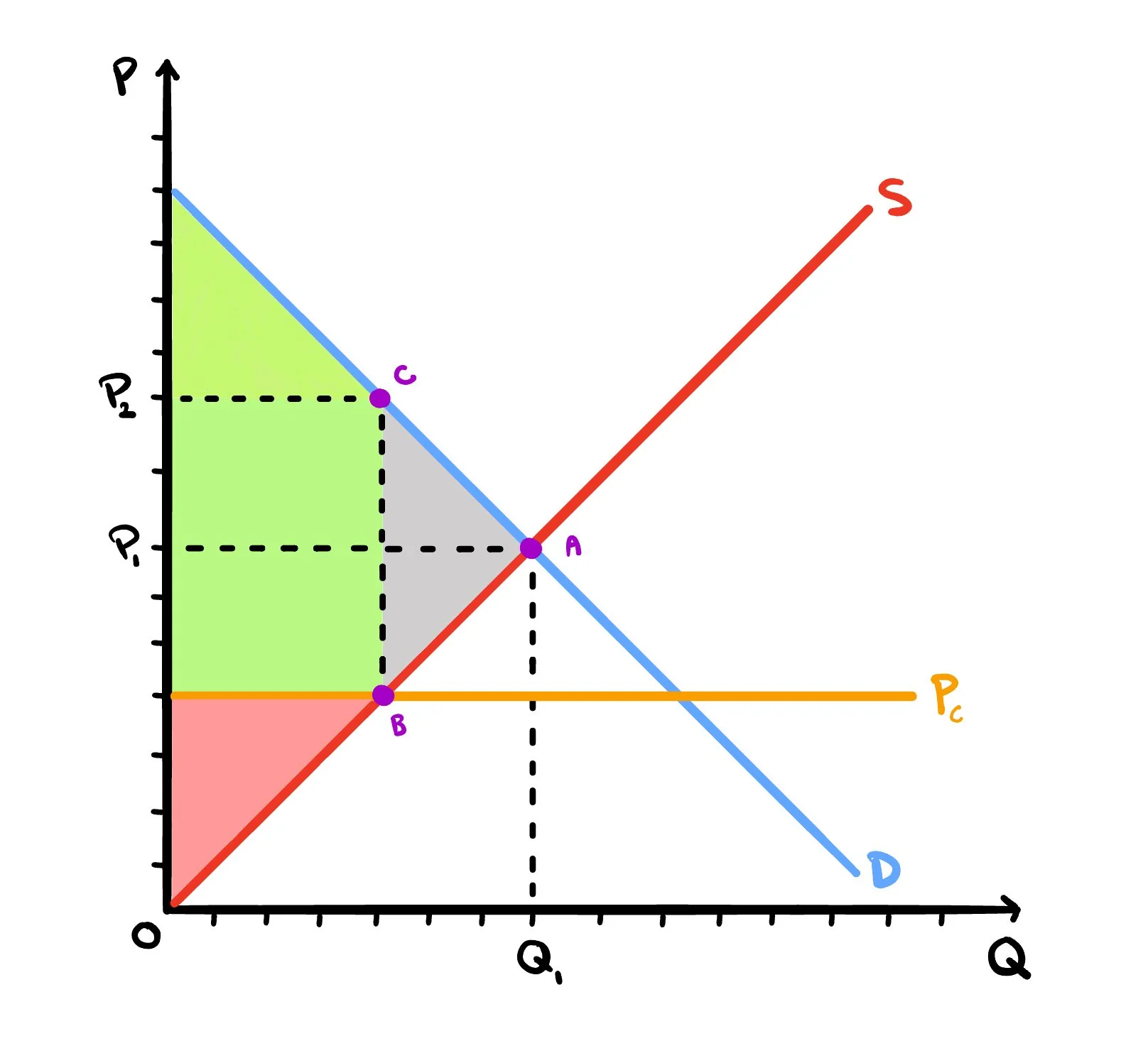

Key Graph to Remember:

Figure 2. An analysis of a market when a price floor is set

Where:

Green Area = Consumer Surplus (increased)

Red Area = Producer Surplus (decreased)

Grey Area = Welfare Loss

-

Description text goes here

Example:

A government caps the price of insulin at $50 per vial, below the market equilibrium of $80. Patients who secure the medication at the lower price experience increased surplus, but others are left without access due to shortages. Pharmaceutical companies, facing lower profits, may reduce investments in future drug development.

Example:

Instead of capping rents, a government introduces a subsidy program for low-income tenants. This increases affordability while maintaining market incentives for landlords, resulting in fewer shortages and higher-quality housing options.