Topic 2 → Subtopic 2.8

Externalities of Consumption

Externalities of consumption occur when the consumption of a good or service creates unintended effects on third parties who are not directly involved in the transaction. These effects can be negative, where consumption imposes costs on society, or positive, where consumption generates broader benefits that are not reflected in market prices. When these externalities are not accounted for in market transactions, market failure arises, leading to inefficient resource allocation and potential welfare losses.

Negative externalities of consumption often result in overconsumption of goods that harm public well-being, such as tobacco, alcohol, and fossil fuels. In contrast, positive consumption externalities, such as education and vaccinations, tend to be under-consumed in a free market because individuals fail to consider their wider societal benefits. Without government intervention, markets may fail to reach socially optimal consumption levels, leading to inefficiencies and long-term consequences.

This article explores the causes and consequences of both negative and positive consumption externalities, their impact on economic and social welfare, and the role of policy interventions in addressing market failure.

Negative Externalities of Consumption

A negative consumption externality arises when the consumption of a product or service imposes additional costs on society that are not reflected in the market price. Individuals who consume these goods make decisions based on private benefits, ignoring the wider social costs their consumption generates. This results in overconsumption, where more of the good is consumed than is socially desirable, leading to long-term harm to public health, safety, or environmental sustainability.

For example, cigarette smoking generates secondhand smoke, which harms non-smokers by increasing their risk of respiratory diseases. Since smokers do not account for these external health costs, cigarettes are overconsumed in a free market, leading to higher public healthcare costs and reduced quality of life.

How Negative Consumption Externalities Lead to

Market Failure

Market failure occurs when individuals consume goods at a level that is above the socially optimal quantity, leading to inefficiencies. In a well-functioning market, marginal social benefit (MSB) should equal marginal social cost (MSC) to ensure an efficient allocation of resources. However, in the case of negative consumption externalities, the marginal private benefit (MPB) of consuming the good exceeds the MSB, meaning that individuals derive more personal benefit from consumption than society as a whole.

Since consumers ignore the external costs, they consume more than what would be ideal for overall welfare. This excessive consumption leads to overburdened healthcare systems, environmental degradation, and lost productivity, ultimately reducing the overall efficiency of the economy.

The Environmental and Social Impact of Negative Consumption Externalities

Negative consumption externalities extend beyond public health to include environmental and social costs. The excessive use of private vehicles, for instance, contributes to air pollution, traffic congestion, and carbon emissions, accelerating climate change. Because consumers base their decisions on private benefits, such as convenience and speed, they ignore the long-term societal damage caused by their consumption choices.

Social costs also arise when individuals make irrational consumption decisions influenced by addictive behaviors or short-term gratification. Junk food consumption, for example, contributes to rising obesity rates, increasing healthcare costs and reducing workforce productivity. While the private benefit of consuming fast food is immediate satisfaction, the social cost includes higher rates of chronic illnesses and public spending on medical treatment.

Positive Externalities of Consumption

Unlike negative externalities, positive consumption externalities occur when the consumption of a good or service generates additional benefits for society beyond those received by the individual consumer. However, because these benefits are not fully reflected in market prices, individuals tend to underconsume these goods, leading to a suboptimal allocation of resources.

Education is a key example of a positive externality. When individuals invest in education, they gain personal benefits such as higher earnings and career opportunities. However, society also benefits in the form of a more skilled workforce, lower crime rates, and greater civic engagement. Since these broader benefits are not fully captured in private decisions, education is typically under-consumed in a free market.

The Economic and Social Benefits of Positive Consumption Externalities

The underconsumption of goods with positive externalities leads to missed opportunities for economic growth, improved public health, and social stability. Healthcare services, vaccinations, and public transportation systems all provide benefits beyond those received by individual consumers. When individuals choose not to get vaccinated, for example, they increase the risk of disease outbreaks, which affects the entire population.

Public transportation is another example of a good with positive externalities. When more people use buses, trains, or cycling infrastructure, it reduces traffic congestion, pollution, and dependence on fossil fuels. However, because individuals may prefer the comfort of private vehicles, public transportation systems often struggle with underuse, requiring subsidies or policy support to remain viable.

Government Policies to Address Consumption Externalities

Governments intervene to correct market failures caused by both negative and positive consumption externalities. To reduce negative externalities, they may impose taxes on harmful goods such as cigarettes and alcohol, increasing their cost and discouraging excessive consumption. Regulations, such as banning smoking in public places or restricting the sale of harmful substances, further limit their social damage.

To encourage positive externalities, governments may provide subsidies or direct funding for beneficial goods and services. Scholarships, free public healthcare, and infrastructure investments make socially beneficial goods more accessible and affordable, increasing consumption and improving economic welfare.

Challenges in Implementing Consumption Externality Policies

Despite their effectiveness, interventions face resistance from industries and consumers. Higher taxes on harmful goods often lead to black markets and illegal trade, as consumers seek cheaper alternatives. Similarly, regulations can reduce consumer choice, sparking public opposition.

For policies that promote positive externalities, the challenge lies in funding. Public healthcare, education, and transportation require significant government expenditure, often leading to debates over taxation and budget allocation. Policymakers must balance efficiency, social welfare, and economic growth when designing interventions.

Example:

A city experiences rising hospital admissions due to respiratory illnesses caused by secondhand smoke. Non-smokers, despite never purchasing cigarettes, bear the health consequences and increased medical expenses, illustrating the unintended social costs of tobacco consumption.

In Summary:

Externalities of consumption play a critical role in market failure, as individuals make decisions based on private benefits while ignoring broader societal impacts. Negative consumption externalities lead to overconsumption of harmful goods, while positive consumption externalities result in underconsumption of socially beneficial services. Governments intervene through taxation, subsidies, and regulation to shift consumption toward socially optimal levels. Despite challenges in enforcement and funding, correcting consumption externalities is essential for long-term economic stability, public health, and social equity.

Key Graph to Remember:

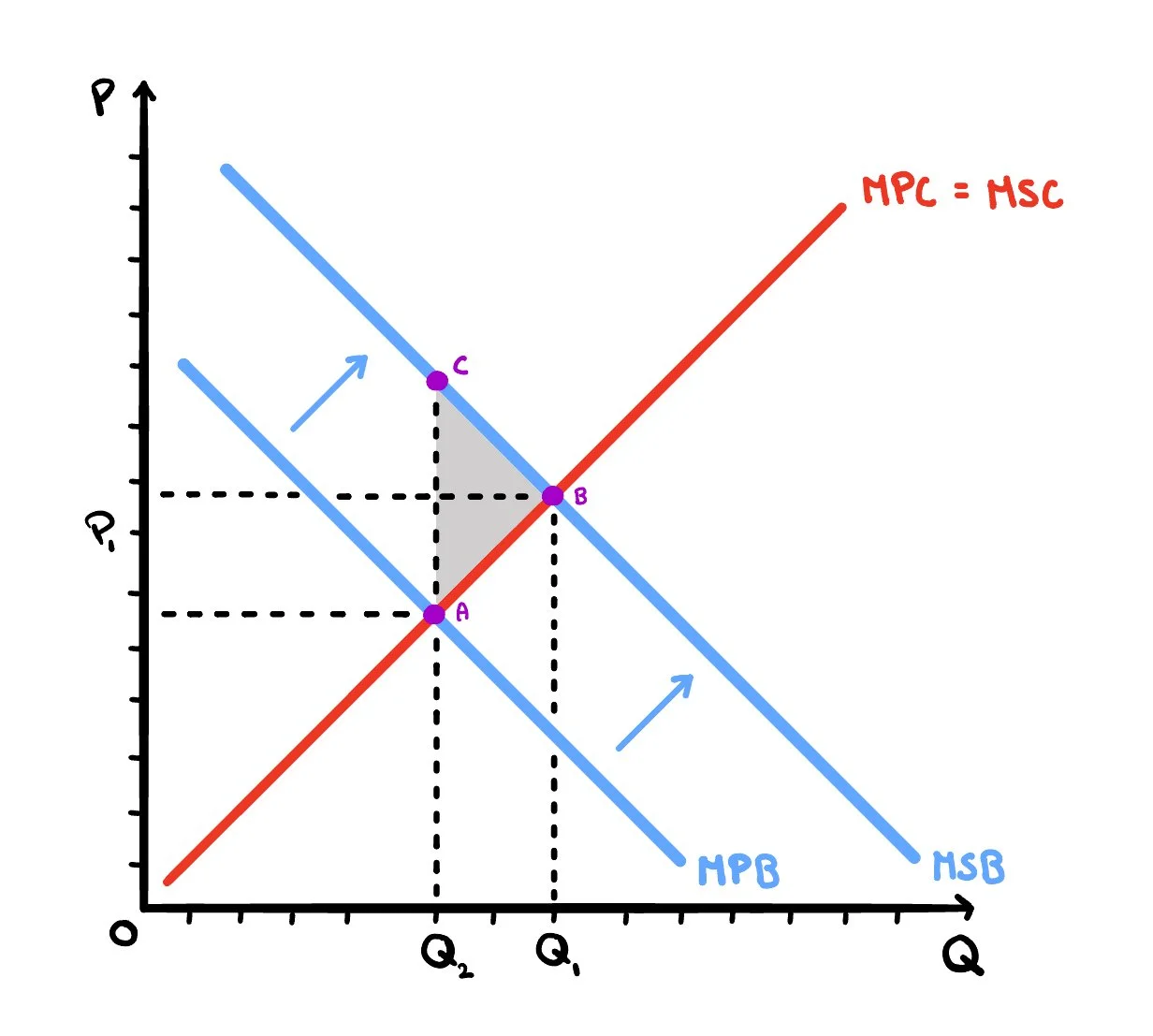

Figure 1. A graphical representation of a negative externality of consumption

Where:

MPB = Marginal Private Benefit (Relatively High)

MSB = Marginal Social Benefit (Relatively Low)

MPC = Marginal Private Cost (Constant)

MSC = Marginal Social Cost (Constant)

-

This graph shows how the private consumption of a good can harm others in society, creating a negative externality of consumption. When individuals make decisions based only on their personal benefit, they often ignore the external costs imposed on third parties. This leads to overconsumption, where more of the good is consumed than is socially desirable, and results in a loss of overall welfare.

The marginal private benefit (MPB) curve represents the benefit consumers feel they receive from each extra unit of the good.

The marginal social benefit (MSB) curve lies below the MPB curve because it subtracts the external harm caused to others (e.g. secondhand smoke, alcohol-related accidents).

The gap between MPB and MSB shows the external cost per unit — harm that is real but not paid for by the consumer.

The marginal cost of production remains unchanged in this case, as the externality comes from consumption, not production.

Because the market only considers MPB and not MSB, it leads to too much consumption, beyond what is best for society.

This creates a welfare loss, meaning society loses potential value because the extra consumption causes more harm than good.

Without intervention, the market fails to reach the socially efficient outcome, suggesting the need for policies like indirect taxes, bans, or public education to reduce consumption closer to the optimal level.

Key Graph to Remember:

Figure 1. A graphical representation of a positive externality of consumption

Where:

MPB = Marginal Private Benefit (Relatively Low)

MSB = Marginal Social Benefit (Relatively High)

MPC = Marginal Private Cost (Constant)

MSC = Marginal Social Cost (Constant)

-

This graph shows how the consumption of certain goods can create additional benefits for society that are not considered by individual consumers. When people base their consumption choices only on personal gain, they tend to consume less than what would be ideal for society as a whole. This leads to underconsumption, where the true social value of the good isn’t fully captured by the market, resulting in a loss of potential welfare.

The marginal private benefit (MPB) curve represents the benefit that individuals personally receive from consuming one more unit of the good.

The marginal social benefit (MSB) curve lies above the MPB curve because it includes external benefits that others in society enjoy (like improved public health from vaccines or education).

The gap between MSB and MPB shows the positive external benefit per unit — value added to society that the individual does not take into account when deciding how much to consume.

The marginal cost of production remains unchanged here, since the externality comes from the consumption side, not from how the good is produced.

Because the market only considers private benefits, it results in too little consumption, failing to reach the level that would maximize social welfare.

This leads to a welfare loss, where society misses out on valuable benefits that could have been achieved through higher consumption.

To correct this, governments can intervene through subsidies, public provision, or awareness campaigns to encourage greater consumption and bring the economy closer to the socially optimal level.

Example:

A nation with high levels of alcohol consumption faces increasing incidents of drunk driving, leading to traffic accidents, higher insurance premiums, and law enforcement costs. The economic burden falls on society rather than just the individual consumers, demonstrating the inefficiency of an unregulated market.

Example:

A country subsidizes higher education, but funding constraints force the government to raise taxes. Some taxpayers object, arguing that they should not have to pay for services they do not directly benefit from, highlighting the complexities of redistribution policies.